Fast Company recently reported that contractors at multiple delivery platforms have partnered with labor advocacy group Working Washington to demand a $15/hour minimum wage across the entire gig economy.

What’s up for debate?

Not every platform company relies on contractors. Some, like Lyft and TaskRabbit, have formal contractors, while other platforms like Atlassian and Shopify look after communities of external developers who are not ‘contractors’ per se but create value through their platforms. However, all platform companies can learn from this debate.

The three involved in this debate — Instacart, DoorDash, and Amazon Flex — pay contractors on a per-hour or per-gig basis, guaranteeing a minimum level of pay per job. However, they’ve been criticized for using customer tips to cover part of this minimum per-job fee, “batching” multiple deliveries into one assignment so the per-gig cost is lower for the platform, and not covering worker expenses like vehicle maintenance and gas money.

Advocates for the contractors say this practice is a way the platforms pass payroll costs on to the customer instead of paying workers a fair wage, and are seeking a $15/hour minimum wage, plus reimbursement for any expenses incurred by an assignment.

Why SaaS platforms should be watching this story closely

True platform companies are not just self-contained ecosystems. They attract a diverse group of creators and consumers, operate app marketplaces that accelerate value-exchange and generation of economic activity and wealth, and are governed by a set of shared behavioural standards.

Instead, true platforms are akin to micro-economies. An economy requires the “management of resources … with a view toward productivity” — in a platform ecosystem, supply, demand, and value exchange must all work in harmony. In addition, platform companies must help to build trust and goodwill between consumers, and service providers like contractors. Without this trust, supply and demand dwindles over time and — poof! — that’s the end of the platform.

While not every platform formally employs contractors, all tend to serve multiple types of creators and consumers. At HubSpot (where I work), because we’re a SaaS platform with open APIs and hundreds of partners participating in our technology programs, our constituents include not just our customers, but also venture-backed SaaS businesses, consumer platforms, and indie developers who leverage our APIs to build valuable, niche solutions for our mutual customers.

These aren’t formal “contractor” groups, but they are certainly people we have a commitment to serve well. If the right economic incentives do not exist within the platform we’re building, platform participants won’t succeed — and neither will we.

Having been part of several platform teams at Facebook, Intercom, Zalando, and HubSpot, there are two things that resonate with me from this debate:

1) Successful platforms give participants the freedom to set their own prices, when possible

Pricing is at the core of this debate. Contractors feel the price set for their work is unfair and too low, and I am guessing the platform companies involved feel they have “optimized” payments for the value consumers are getting. Clearly, the two groups do not agree on what “price” accurately represents the value each group is creating and exchanging.

One way platforms can avoid this kind of disagreement is by allowing end users and/or creators to set their own prices. This has worked well at companies like Fiverr and Upwork, which both migrated from a top-down pricing model to a more fluid system where pricing is mutually set by contractors and buyers.

Another benefit of this approach is that any participant, anywhere in the world, can compete equally for the same business, and not just on price. This controls for economic imbalance, to a certain extent — $100 USD has a different value in the United States than in the Ukraine, and even within countries the same rules can apply (having lived in London, and visited Liverpool, £1 buys you less in the former, and more in the latter).

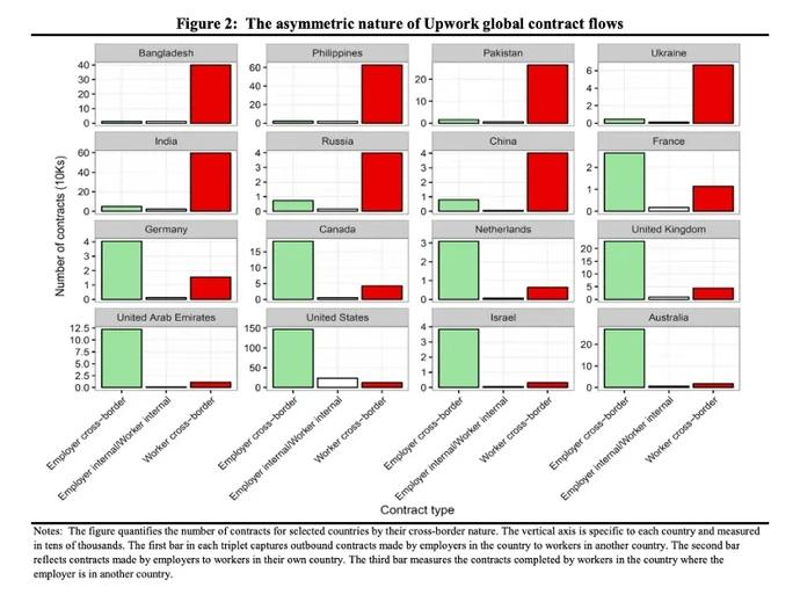

In their paper “Digital Labor Markets and Global Talent Flows,” John Horton, William Kerr and Christopher Stanton demonstrate that the geographical flow of labor on Upwork is asymmetric:

The asymmetry in these labor flows demonstrates the important reality that wealth is created when platforms maximize connections between creators and consumers — regardless of physical location. The vast majority of Upwork’s value exchange happens across borders, and it’s this set-your-own-price model that’s created even more opportunities for creators and consumers to connect and transact with each other.

Through this transition, Upwork has sidestepped the potential stumbling block of setting a ‘wrong’ or unfair price for services provided through their platform. Consumers and creators apply their own unit of value to each exchange, upfront. The platform “lets the customer decide.”

2) Before monetizing, consider all constituents’ interests

At a product company, the value exchange between vendor and buyer is very simple — consumers expect a quality product from the vendor, and vendors expect to be paid.

This gets more complicated when you’re a platform company. Not only do providers sell their product to consumers, they must also look after their own relationship with third-party creators who build on top of the platform, provide mechanisms for those creators to connect with consumers, and ensure the quality of goods and services delivered via the consumer-creator relationship.

Each of these value exchange events is an opportunity to generate revenue, which is one reason we’re seeing more and more companies aspire to become platforms. But a common pitfall of monetization is that sometimes, it serves one group’s interests at the expense of another’s.

Platform companies looking to monetize their ecosystems would do well to preempt similar issues by ensuring they create a fair and balanced playing field for all participants. While platforms may earn more in the short term using aggressive monetization tactics, the ones that fail to build long-term goodwill, trust, and positive financial outcomes for creators will result in the collapse of their micro-economy — which, in turn, negatively impacts the experience for consumers, as niche needs will no longer be served.

What do platforms owe to their micro-economies?

This debate is the latest permutation of a question more and more platforms will face:

When a platform creates a new type of behavior, are they responsible for regulating that behavior on — or off — platform?

We’ve seen this discussion unfold as companies like Facebook and Twitter have taken heat for failing to stop hate speech, harassment, and misinformation on their platforms. In this scenario, platforms are contending with their own policy decisions rather than external unintended consequences, but I’d argue that the most important takeaway is a natural extension of this broader question.

The individuals responsible for monetization and governance decisions at platform companies have to remember that at the end of the day, all platform participants are humans. They’re more than the bits and bytes logging each delivery made or order completed — they’re real people, with bills to pay and families to feed. They also happen to be the reason that platforms evolve and grow in the first place. The decisions we make can have profound effects on their lives, and it’s our obligation to be transparent and upfront about how we’ll interact with them so they can make an informed decisions on how and where to spend their working hours.

The most successful platforms are the ones where all participants feel they are being treated fairly and where value is distributed equally. Deliberately creating parity between constituent groups, and ensuring each cohort’s interests are protected isn’t just the right thing to do — it ensures your micro-economy will be around for far into the future.