What is a Platform?

May 24, 2017

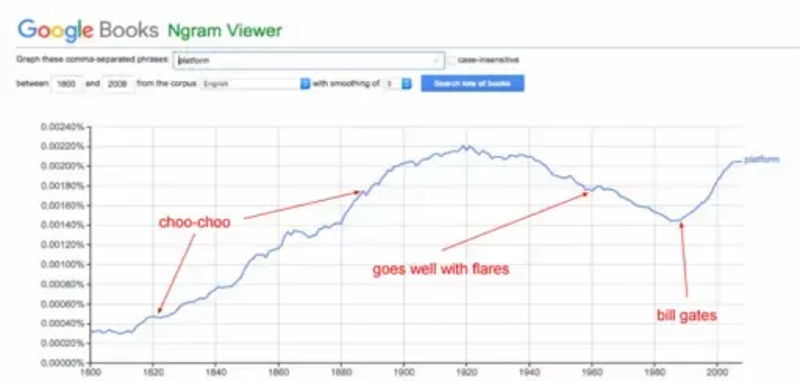

From enabling passengers to embark and disembark trains, to vertebra-crushing shoes, and operating systems like Microsoft Windows, “platform” has been used to describe many different things, in many different contexts, over a long period of time.

Lately, its meaning has become even more complicated and diluted.

Technology companies — particularly SaaS startups — are using “platform” to describe website builders, CRM solutions, To-Do list apps and everything in between, even when “tools” or “programs” are more accurate ways to describe what they’re building.

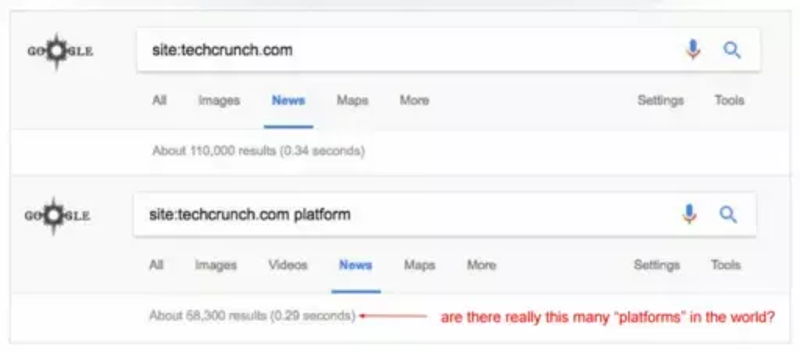

Try a Google News search for “techcrunch.com platform”. Are there really over 50,000 true platforms in the world? By true, I mean companies comparable to Facebook, Google, Amazon, Airbnb, Uber, and Microsoft. Drop two zeros, and we’re getting closer to a realistic number.

Most startups are really building products, not platforms.

“Platform” is being misused for one reason, and one reason only: funding. Think about it — you’re more likely to gain more column inches and funding by aspirationally comparing your SaaS startup with Microsoft Windows vs comparing it with Microsoft Encarta.

One is a single use product, the other is a micro-economy. Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg aren’t just product builders, they’re economy builders.

What platforms really are

A “true” platform in the technology or economic sense is more accurately called a “multi-sided platform.” Microsoft Windows, Google Android, Apple iOS, Facebook, Uber, and WeChat are all multi-sided platforms. Whilst they may sound complicated and modern, multi-sided platforms are thousands of years old and easy to understand. Here’s some familiar examples.

Arguably the world’s oldest platform, money has helped consumers (buyers), merchants (sellers), and banks exchange value across the world for thousands of years. William Stanley Jevons once described money as having four functions: a medium of exchange, a common measure of value, a standard of value, and a store of value.

Money makes it efficient for merchants to trade with each other, consumers to trade with merchants, and consumers to trade with each other. We store our money in banks and under our beds, using cards and cash as tools to exchange monetary value with each other. Global trade can’t happen without it.

Since the 1920s, television has delivered news of John F. Kennedy’s death across the world in real time, entertained billions in their homes with soap operas and movies, and taken us deep into parts of the world we might never visit through documentaries from presenters like David Attenborough.

It’s a mass telecommunication platform, providing entertainment and educational value for viewers, communication value for advertisers, and distribution value for content creators. In a new age of always-on high speed broadband, companies Netflix continue to evolve the meaning of “television.”

Shopping centres (or shopping malls depending on where you’re from) sprung up in 1950’s America to address the needs of people migrating from inner cities to suburbia. Victor Gruen, architect of the first fully enclosed, climate-controlled shopping center in history referred to early shopping centres as “multifunctional centers”, an antidote to the disconnected stores and services scattered across the “suburban labyrinth”.

Today, shopping centres around the world are a “third place” for billions of people — one central platform for people to connect, transact, and eat.

The intangibility of platforms

As you may have noticed by now, platforms aren’t real, physical things. You can own, touch and feel a £1 coin, but that’s just one component of the platform that is “money”.

When businesses “advertise on television”, can they point to a single physical representation of what they’re advertising “on”? We gaze at television sets, but these sets would be useless in isolation — we need stations, programmes, and satellite dishes to get value from them. All components of the platform that is television.

Whilst they contain physical and virtual components, platforms are intangible.

Facebook Platform is intangible. Yes, you can scroll through your Facebook feed on your phone, and read Facebook’s excellent developer documentation, but what you can’t see are the millions of people working for businesses “built on” Facebook platform. These people, the things they design, build, and sell - and the ideas they create - are all core components of the overall Facebook platform.

Even the technology that contains Facebook platform doesn’t exist in one place — it’s distributed all over the world in Facebook’s data centers, independent apps hosted on Amazon AWS, on billions of mobile phones, and in physical locations.

Just like an economy or a country, a platform is an idea. And ideas are intangible.

What is a Platform?

Platforms are not “designed” upfront — they evolve organically over time. But every true platform — from shopping centers to technology platforms like Salesforce, Atlassian, Facebook, and Google — all share three common traits.

True platforms serve multiple types of consumers

Compared with products, which typically serve one type of consumer (who typically pays money for the product), platforms serve multiple different types of consumers at once. The volume and type of consumers typically increases as the platform evolves. Uber is a perfect example of this.

Uber connects people who need to be transported from one place to another with other people who can take them there. Through integrations with Uber’s APIs, United Airlines add value to their customers by making it easy to book a ride through the United Airlines app when they land.

The Washington Post supply news to Uber riders through Uber’s app when in transit, increasing distribution for their content, and helping riders make more use of their travel time.

Suppliers like Firestone, Valvoline, Stride Health, AT&T and Verizon are partners of Uber, who connect these partners with their driver network in exchange for negotiated group discounts.

Drivers, commuters, insurance companies, fuel suppliers, publishers, and airlines are all consumers of Uber’s platform. These multiple consumer types exhibit different needs, are incentivised differently, and consume the platform in many different ways.

True platforms facilitate efficient value exchange

With a vast array of different platform consumer types to serve, great platforms excel at providing tools and services to facilitate value exchange between these different types of consumers through a variety of platform marketplaces.

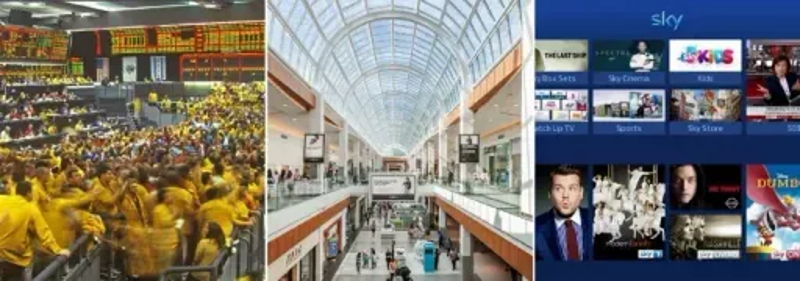

The Foreign exchange markets facilitate the exchange of currencies — money — in real-time across the globe. Banks, consumers, and businesses can exchange one currency for another through software, in person, and through currency trading floors.

Shopping centres facilitate value exchange between merchants, consumers, and advertisers through a thoughtfully and cleverly designed experience. Most are designed to funnel consumers through pre-defined routes, making it easy for consumers to discover the stores and services they might need, so they can exchange value with merchants quickly and easily.

Telecommunications companies like Sky make it easy for consumers to find the most relevant entertainment, news, and documentary programmes they might need, through personalised discovery tools. Movie studios, content aggregators like Netflix, and cable networks leverage these tools to drive distribution of their content and services. Advertisers leverage these combined audiences to market and sell their products to consumers.

True platforms exhibit shared common standards

Every economy has a set of laws and standards to ensure the participants in the economy can transact fairly, quickly, and easily.

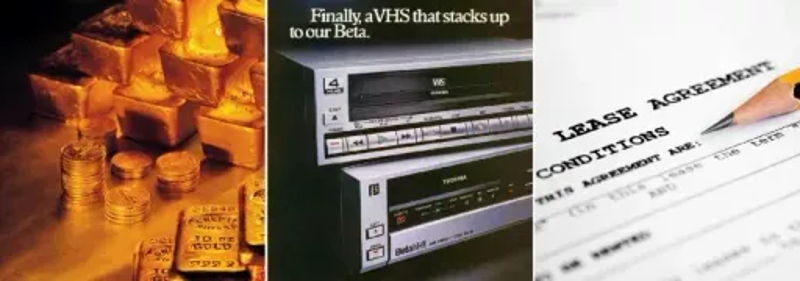

Transacting through the platform of money requires participants to adhere to a common set of standards like The Gold Standard, territories like Europe and the United States, currencies like the Euro, Dollar, and Pound, and concepts like inflation and quantitative easing.

Television holds participants to an ever evolving set of shared common standards. Content producers need to understand various colour systems like NTSC, PAL, and SECAM. They need to understand frame rates and the meaning of telecine. Hardware manufacturers and content distributors need to understand UHF, VHF, DVD, and HDMI — if these standards didn’t exist, interoperability would be non-existent.

Shopping centre merchants need to understand and adhere to a wide variety of local and international trading laws. Commercial lease agreements set out the obligations and requirements of merchants and landlords. Zoning laws set out requirements for access, parking, and transportation — all vital elements to help drive distribution for the products and services being traded through the platform.

When is a platform a platform?

A true consumer technology or B2B SaaS platform is one which exhibits each of these three traits.

If you’re serving multiple different types of consumers like developers and platform partners, through building partnership teams, hiring developer advocates, and connecting platform participants at events and summits, you’re probably building a platform.

If you’re facilitating efficient value exchange through building and operating an app marketplace like Shopify’s app store or providing contextual discovery tools, connecting 3rd party integrations and tools to the customers who need them most, you’re probably building a platform.

If you’re invested in building a shared set of common standards through standardised internal and external facing APIs, documentation, terminology, and “dogfooding” the programmatic surfaces that developers and partners interact with, you’re probably building a platform.

Everything else is a product.

Sign up for our newsletter

App marketplace research and insights to your inbox every week.